Mariners harnessed knowledge from the skies and steered their vessels to victory

Date : 04/05/2024

The gentle sea at that time was soaking herself in the luminance of the Sun. It sparkled like sequins placed all over the great blue attire, but at that moment, it was crimson red.

A boy-man was looking at the horizon. It was looking endless as his thoughts were. In a few days, he is about to take his first journey to that vast infinity and was asked by Moopan to gaze at a star-studded sky that night.

Moopan is very old, old enough many in the village claim he is more than a hundred years old. He is profoundly mystic and doesn't speak much. You would mostly find him in the temple of Neelayadhakshi or in one of the creeks where Kaveri empties herself. He gazes at the sky and draws various sketches on the wet soil, multiple arcs, intersecting lines, which does not make any sense. When asked, the answer would be his profound and disturbing silence. Moopan has accompanied travellers for many voyages. In one of those voyages, he faced a shipwreck. All were assumed dead. Except him. One fine day, he just rose from the sea. He knows the Vanga kadal (Bay of Bengal) very well. And he is the profound master in keeping time and watching the sky. He speaks to turtles as though both know each other for a very long time and sometimes gives them medicines. His name was Arata Mooki, but after the shipwreck incident, everybody calls him Moopan.

Neelan was deep in his thoughts, but at times amidst all these uncertain and anxious moods, he remembered Kumudha. Her dark wide eyes and her eyebrows had shrunk with the query of “When are you going to be back?”

Let's leave Neelan to his musings and pivot ourselves to the journey he is about to endure. He's going to cross the Vanga Kadal (Bay of Bengal) and reach the kingdom of Sri Vijayam in the islands of today’s Sumatra and Java.

The voyage would generally commence before dawn on the eastern sky right after sighting Mrigasira (Bellatrix), Agastya (Canopus), Arudhra (Betelguese), and Kruttika (Pleiades) near the bow of Arudhra on the Southern horizon.

This journey commences well before Margazi Pournami (full moon) of Arudhra darshan (The Thiruvathirai festival). This is when star Arudhra is sighted at dawn for the last time of the year in the eastern sky. Srilankan Tamils used to navigate to Chidambaram (in Tamil Nadu) from Jaffna to participate in the Thiruvathirai festival even till the end of 16th century.

Interestingly, the magnificent Pallava's Gangadhara Shiva in the Kanchi Kailasanatha temple is assumed to be depicted with Orion belt, two dogs as Punarpoosam and Poosam, and Ganga as Kruttika. These are the stars that were sought after before setting on the Margazhi voyage.

Picture of Gangadhara Shiva in the Kailasanatha temple in Kanchipuram

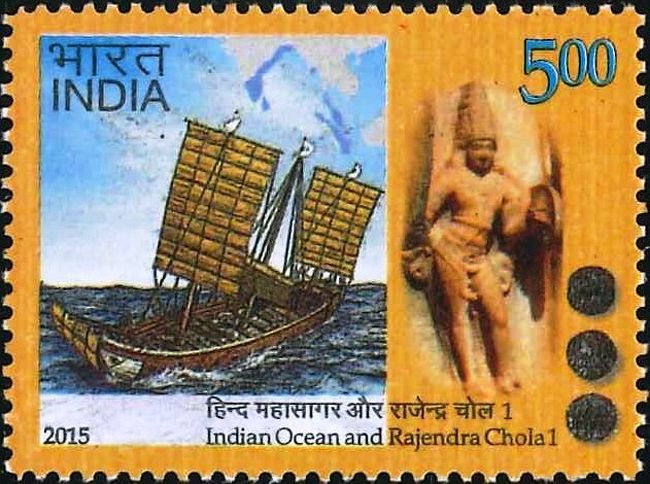

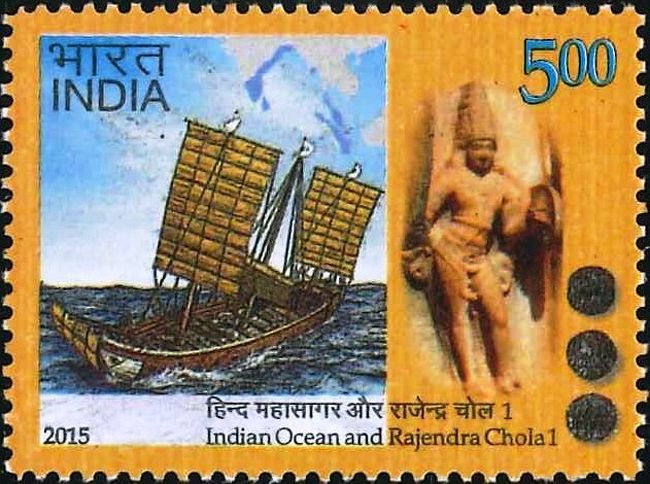

The port of embarkation was mostly from Nagapattinam. It was the preferred port for Chola emperor Rajendra's victory towards the east. The entire east from Ganga's mouth till the end of Sri Lankan coast was under his control. And the ships could have ventured in to the sea from anywhere along these lines. The Bay of Bengal would have been his pond.

And if this journey begins after Margazhi, then the star Sharavana (alpha Aquila) raising in the eastern sky at dusk becomes the indicator. By then, Arudhra would be seen in the western sky during dusk. The later the season, the more southerly the latitude.

Now, the ships would move towards Sri Lanka. And the southward sail would not exceed Kalmunai, or after that during the season, it would be Tirukoil of Sri Lanka's eastern coast. The ships would set on the eastern voyage towards Sumatra, before crossing Sangam Kanda Turai at Tirukoil. That would be near today's Batticaloa. The direction would be to follow vada kondal (the prevailing wind) and vada olini (the currents).

It's obvious why the Cholas had the coastlines under their control. One of the main ports was Triconamalai (Trincomalee) where the river Mahaweli Ganga originating from Kandy empties. The river’s mouth directs Cholas straight to their Sri Lankan capital Polonnaruwa. Trincomalee was much famous for its oil and coal refilling, till it was bombarded by Imperial Japan in World War II targeting British ships there. It came to be known as the Pearl Harbour of British.

Armed with the square of rectangle sails (the triangular lateen sails were not in use then), they would sail nearly parallel to the equator circles around 5 to 7 degrees north.

The stars in the Orion belt, Ursa major (Sapta rishi Mandal/ Kappal Velli) were observed and used for east to west sailing much close to the equator, making it more or less parallel sailing. In the early morning hours, the use of Mrigasira and Arudhra till January and Tiruvonam in the evening sky ensured a due west to east smooth sailing. With the help of the Equatorial westerlies, they would land in the southern end of Sri Vijaya’s Sumatra. If they start early, they would reach the north of Sumatra. With favourable wind systems and currents, they would reach the destination in 12 to 15 days.

Additional identifications were made by utilising other stars in Ursa Major. Arundhati was called Uthra meen (vada velli) or north star in India's southern side, mainly because Dhruv was not visible traveling at a latitude below 8 degrees north. The Dhruv (Pole star) is 89 degrees north, and it is most favourable in finding out latitude subjected to minor error. While it can be sited at a reasonable altitude, its height falls progressively towards the equator. Since the interstellar distances are constant, making out the difference between Arundhathi and Dhruv in the arc, the value of 15 virals would help us determine the latitude. Viral being measured as 1/8th of yamam.

The distance cannot be physically measured, and hence the relative normal sailing distance under fair sea and speed under the watch of three hours becomes the versatile yamam. Eight yamams constituted a day's sail. A day was from sunrise to the next day's sunrise (not midnight to another). Initially used to measure time, it was started to be used to measure the distance which was covered in three hours. In seamen's language, an angular arc is 1/8th of viral, and yamam equivalent to 20 km.

Precise measurement of the moment was never a concern of the traditional seamen who have taken up the responsibility of ensuring everybody's safety.

An early system of measure of the finger unit and closed fist held horizontally at the stretched hand distance was equal to 4 viral. And over time, it developed into simple hand tools. The Mediterranean seamen, especially the Portuguese, talk of using such a device known as Kamal by Arab mariners or Rapalagai (in Tamil). A rectangular board with a hole in the exact center runs a string knotted and fixed at the board's back. The string itself has various knots without any proportion, as they indicated the specific ports, determined and set by repeated expeditions. Since the thread is bound to have the curve, the cross-staff was later used, and in Kerala, it was called Kau-kutty.

Traditional mariners develop a practical understanding of the starlit skies through repeated observation of the sky and harness the knowledge to steer the vessels. Lying on the back deck of a ship and to watch the starlit nights at leisure and they were able to identify specific stars and track their motion from eastern skies towards the western horizon and note down the constancy in their position. Ancient Indian navigators regularly traversed the sea, finding new routes for trade and cultural exchanges, and certainly knew their art of navigation using heavenly bodies.

They were smart to assess with their practical voyage experience that they would overshoot the position sailing along the rhumb on a northerly voyage and hence reduced their time of sail, and they would have to travel a bit more when traveling south on a constant bearing.

They somehow knew the meridians converged. Travelling east to west was less complicated than North-south, and the longitude assessment eluded the sailors till the nineteenth century. The Indian mariners never used longitude but found their indigenous solution, while the voyage has to be made north to south or otherwise.

The sea route, sans pirates, was safer than the Silk road that was often disrupted with unpredictable political borders. After the Tang dynasty in China, the Sangs laid more emphasis on sea trade. Rajendra Chola's expeditions should be interpreted in this context of an international trading system and their linked markets in China.

Let's tread across more Indian maritime trade with a particular reference to Cholas, Sri Vijaya, Chinese, and Arabs. Their commerce and their natural science, in the coming parts.

Nithya Raghunathan is a banker, a bibliophile and an heritage and culture enthusiast

References:

1) Books published by Maritime History of India authored by Prof. B. Arunachalam.

2) The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A Study of T’ang Exotics by Edward H Schafer

3) Nagappattinam to Suvarnadweepa: Reflections on Chola Naval Expeditions

4) Maritime lectures published by Maritime History Society.

Tags :

Note: Your email address will not be displayed with the comment.