The story of how Sir Nair took on the mighty British empire

Date : 18/05/2024

On the 13th of April 1919, which corresponded to Baisakhi, the Punjabi New Year, hundreds of Indians congregated in Jallianwala Bagh to protest the recently passed Rowlatt Act.

The Act enabled the British government to restrict the movement of any Indian within the country by ordering them to stay within a specified area, possibly away from their workplace and without being entitled to a hearing in a court of law. Police could arrest anyone they found suspicious without needing a warrant, people could be fined without explanation and their properties searched. Unsurprisingly, Indians revolted against the law and nationwide strikes ensued. The situation was worse in Punjab because nearly 400,000 Punjabis were forced to join the army to fight World War I, their wheat was forcibly exported to feed British soldiers and Sir Michael O'Dwyer, the Lieutenant Governor of the Punjab was making insensitive speeches about the rationality of the Act. The protests were so intense that O'Dwyer had to bring in Brigadier General Dyer, a military officer with a reputation of short temper and ruthlessness, to control the riots in Amritsar.

Though martial law was imposed in Amritsar at the time, nearly 25000 protestors including Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims gathered in the Bagh by afternoon. This included women, children, and infants. No violence was intended, and many were there only to celebrate the new year. By 4.30 pm, Dyer brought in ninety armed soldiers and stationed them at the entrance to the Bagh, making escape impossible. Without any notice, the policemen fired non-stop for 10 minutes, exhausting nearly 1650 rounds of ammunition. Indescribable horror followed. Some people lay flat on the ground to escape bullets. Those who tried to climb up the wall of Bagh were all shot. Several threw themselves into a well inside the Bagh to escape the firing and those who jumped in first died from the weight of those who jumped after them. Moulvi Gholam Jilani, a participant, later wrote, “I ran towards a wall and fell on a mass of dead and wounded persons. Many others fell on me… There was a heap of dead and wounded over me, under and all around me. I thought I was going to die”. Gen Dyer later submitted a report to the government justifying his action thus: “I realized that my force was small and to hesitate might induce attack. I immediately opened fire and dispersed the mob. I estimate that between 200 and 300 of the crowd were killed”. His lack of remorse was clear in his subsequent writing: “I think it quite possible that I could have dispersed them perhaps even without firing. But I didn’t do so because they would all come back and laugh at me and I considered I would be making myself a fool”.

The massacre was followed by a series of violent acts against Indians, such as making them crawl on all fours and salute all Englishmen. Despite the cruelty and callousness of the massacre, the British administration ensured that the event was downplayed by the local newspapers. Many Indian newspapers were asked to stop printing altogether and English journalists who were sympathetic to the plight of Indians were sent back. The 'Report on the Native Papers', a routine communication informing the administrators in London about the activities in India, contained no mention of the massacre. The event was portrayed as an attempt to reinforce British military strength over India to prevent a reoccurrence of the 1857 uprising, and therefore O'Dwyer and Dyer were lauded as British heroes.

What followed was an unexpected series of actions by a constitutionalist and judicial expert from Kerala who staked his entire career and reputation to bring justice to the innocent victims of this crime and to have the British government acknowledge the monstrosity of their actions in order to ensure that Jallianwala Bagh would not repeat.

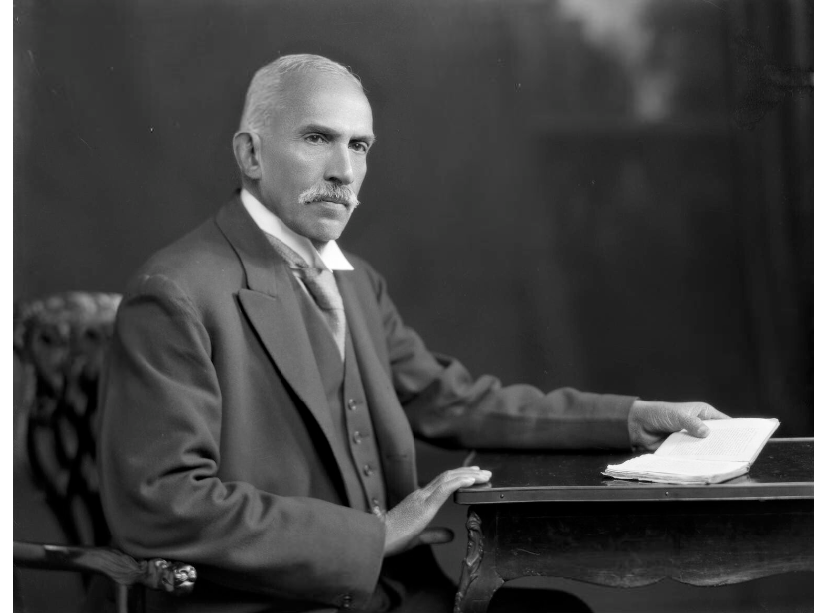

Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair, the only Keralite to ever become President of the Indian National Congress, was born in 1857 in Mankara, a small village in Palakkad district. He studied law in Madras and soon became a judge. He was the first Indian to be Advocate General of Madras, the first Indian judge of the High Court of Madras, president of the Amaravati session of the Indian National Congress, knighted by King George V, and a Member of the Viceroy's Executive Council - a role second only to the Viceroy, the highest position an Indian could dream of in those days. Nair had a reputation of being fearless and razor-sharp in his repartees; his expertise coupled with political influence made him a force to be reckoned with.

Photograph of Sir Nair preserved at the National Portrait Gallery, London

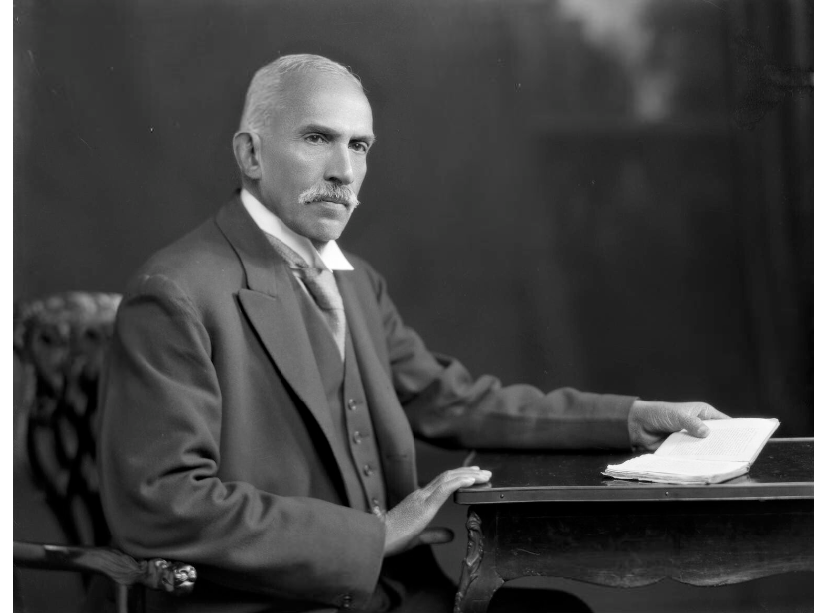

Sir Nair in his uniform as member of the Viceroy’s Council

The massacre occurred when Sir Nair was in the Viceroy's Council. Furious, he resigned in protest. The Viceroy was uninterested in the opinions of Indians and Sir Nair, despite his expertise, was not exempted. Sir Nair's biography, written by his son-in-law and diplomat KPS Menon, narrates how the Viceroy called him in for a final meeting and asked if he could suggest a successor. Sir Nair solemnly replied "Yes" and pointed to the uniformed doorkeeper. The Viceroy shot into a rage while Nair continued, “Why not? he is tall and handsome, wears his livery well and will say yes to whatever you say. He will make an excellent member of the council”.

Sir Nair's resignation had immediate effect: the ban on press was lifted, martial law in Punjab was terminated within a fortnight and the Viceroy was forced to setup the Hunter Committee to investigate into the massacre and other acts of violence in Punjab. Nair was invited to London to present the facts to the British parliament and offered a position in the Council of the Secretary of State for India. In London, Nair presented Dyer's testimony of having planned the shooting in order to create a 'moral impact' on India, and this created a sensation in the British press. The Viceroy had to concede that Dyer's act of massacre and subsequent 'crawling' orders were inhumane, and Dyer was sent back from India. His recommendation for a titled position was withdrawn.

The Hunter Committee report condemned the Bagh massacre and the decision taken by O'Dwyer and Dyer to fire without warning, calling it a 'grave error'. The British parliament, Churchill and the British press condemned the incident, calling for strict penalties against them. Despite the evidence against Dyer, he was not prosecuted or penalized, partly because his actions were condoned by his supervisors and partly because of his popularity among influential British politicians. His failing health gave him an opportunity to resign. O'Dwyer's reputation was tarnished permanently, or so it seemed.

But the story did not end there.

Sir Nair, an ardent constitutionalist, held political views that opposed those of Mahatma Gandhi. He disagreed with the view that the civil disobedience movement, non-cooperation and non-violence were the path to independence, as they could result in bloodshed and riots impacting innocent people. Fearless to the core, he expressed these views in Gandhi and Anarchy which he published in 1922. He devoted a chapter to the atrocities in Punjab and indicated that the atrocities there were committed with the full knowledge of O'Dwyer. O'Dwyer now found an opportunity to redeem himself - he termed Sir Nair's words as libel and threatened legal action if he did not withdraw the book from circulation, apologize and pay a fine. Sir Nair, who never backed down from a fight, disagreed and proceedings were initiated in the Court of the King's bench in London.

The trial that followed lasted over five weeks and was the longest in the history of this court; given the stature of the parties involved, it was followed with rapt attention by the Empire and the people of Punjab. On the one hand, there was a large segment of the British population who still believed that Gen Dyer's actions saved and restored the power of the Empire while on the other hand, people of both nations were sympathetic to the atrocities in Punjab, thanks to Sir Nair's resignation. Sir Nair and O'Dwyer brought in a series of witnesses from India and England. O'Dwyer's witnesses were from the landed higher castes while Sir Nair brought in a variety of affected individuals of all castes and social statuses. The court room was always full, and the audience included luminaries like the Maharaja of Bikaner. Sir Nair and his counsel argued that the statements in his book were factual and published in good faith as a matter of public interest. Fifteen people testified that the massacre was unannounced and that people who were fleeing were also shot mercilessly. Sir Nair's witnesses recounted emotional stories such as being stripped naked, beaten with sticks and having brambles placed between their legs, being handcuffed and made to sit on thorns in the sun, and bent double while holding their ears through their legs. Sir Nair demonstrated that in court and the visual clearly made an impact, as evidenced by the collective gasp that emerged in the courtroom. The opposing counsel made all efforts to make O'Dwyer appear to be a gentleman caught in the crossfire of bad decisions made by Gen Dyer.

Despite strong arguments and a hung jury, the case was brought to a close by both sides agreeing to accept the majority opinion which exonerated O'Dwyer. Several factors contributed to this decision: the case was held in England where O'Dwyer held significant influence, the judge appointed to this case indicated his favor to O'Dwyer from the beginning, and the jury was all British. Sir Nair was asked to pay O'Dwyer a fine of 500 GBP and costs of the case. O'Dwyer agreed to waive all payments if Sir Nair would tender an apology for the remarks made in his book. Sir Nair's rejection of that offer resounded loud and clear in the courtroom. Not only did he pay a fine of GBP 7500, he rejected the option of appealing the case saying, “If there were another trial, who was to know if 12 other English shopkeepers would not reach the same conclusion? ”. Sir Nair was asked “But what about your reputation?”, to which he replied, “If all the judges of the King’s Bench together were to hold me guilty, my reputation will still not suffer”.

Sir Nair’s image on a postal stamp

Sir Nair fought a long and vicious battle single-handedly for what he believed was right. On paper he lost, but in the minds of millions of Indians, he was a winner, a hero who stood up for them when they could not stand up for themselves. The plaque at the entrance to the Bagh museum commemorating Sir Nair is a testament to his efforts. He is truly an unsung hero of our independence.

Despite his failure in a court of law, the O'Dwyer vs. Nair case accomplished Sir Nair's primary objective - letting the world know what had happened in the Bagh, thereby making sure it never happened again. The British press had mixed reactions: those who supported Dyer supported the decision while others who were sympathetic to the Indian mindset condemned the judge's bias and considered it a regrettable misfortune in the history of the British judiciary. Indian newspapers were much more vocal in condemning the judge and the British justice system and although they were disappointed about Sir Nair's failure, their reports raised his stature as a patriot and administrator. Winston Churchill described the massacre in the British parliament as “an episode which appears to me to be without precedent or parallel in the modern history of the British Empire… It is an extraordinary event, a monstrous event, an event which stands in singular and sinister isolation”.

The author is currently pursuing her doctoral studies in Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore

Image Credits: National Portraits Gallery

Sources

Ilahi, S. F. (2008). The empire of violence: strategies of British rule in India and Ireland in the aftermath of the Great War (Doctoral dissertation)

Menon, K. P. S. (1967). C. Sankaran Nair. Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India.

Nair, S. C. S. (1966). Autobiography of Sir C. Sankaran Nair. Lady Madhavan Nair

O'Dwyer, M. (1925). India as I knew it. Constable & Co Ltd.

Palat, R., & Palat, P. (2019). The Case That Shook the Empire: One Man's Fight for the Truth about the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Tags :

Note: Your email address will not be displayed with the comment.