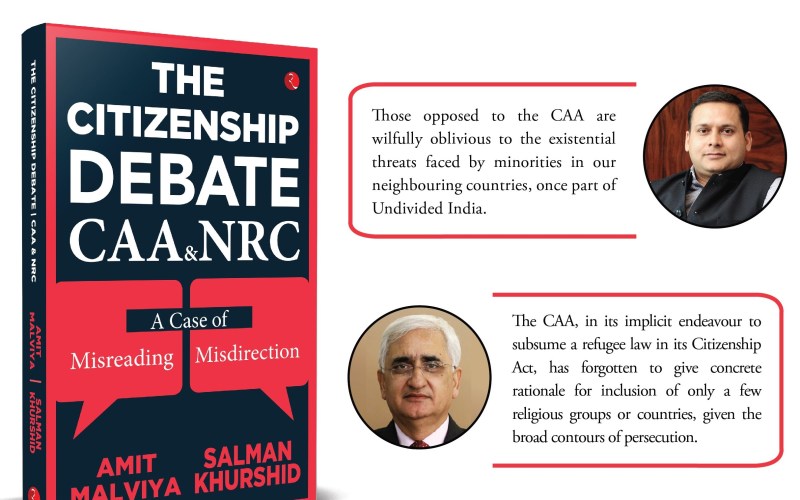

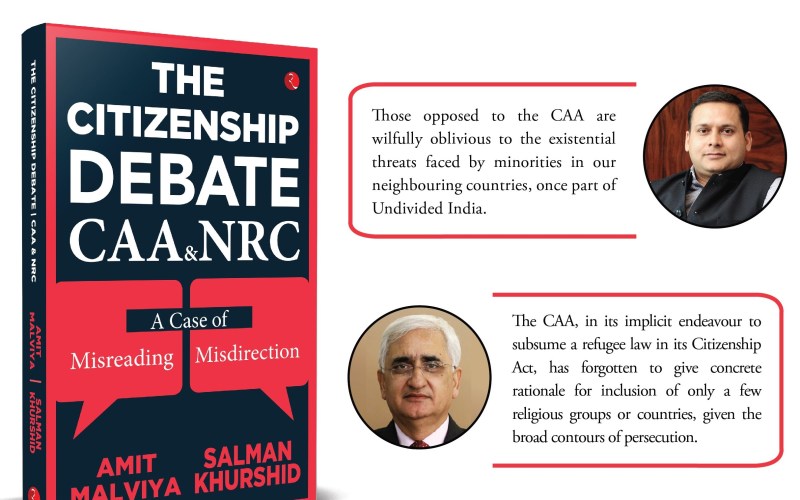

Book Review: The Citizenship Debate: CAA & NRC by Amit Malviya & Salman Khurshid

Date : 10/05/2024

In an era of high-decibel television debates, steered immoderately by belligerent news anchors, it is indeed heartening to see what Amit Malviya and Salman Khurshid have achieved in The Citizenship Debate: CAA & NRC; together, they have produced a remarkable discursive space which allows two radically different viewpoints to coexist, each exercising nearly equal latitude in countering the other. The nobility of the format, of late lost in the rancor of partisan news debates, brings to mind Viplav (1937-48), a popular periodical edited by the legendary Hindi author Yashpal. Yashpal was an associate of Bhagat Singh, an avowed Marxist and a sworn critic of Gandhi. In that sense, he shared with Gandhi a relationship of deep ideological differences, just as Malviya shares with Khurshid. Yet, he never sought to erase the latter from the public imagination, or to obfuscate his ideas with a farrago of accusations. In the pages of Viplav, Gandhian ideas were printed alongside Yashpal’s critique, the contrarian positions commanding equal space. We see something strikingly similar in The Citizenship Debate; while Malviya has written the first part of the book, the second part is authored by Khurshid. This Voltairian respect for views from the other end of the political spectrum is perhaps the most conspicuous and outstanding virtue of the book.

The first half of the book seeks to counter the stock accusations hurled at the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), the National Register for Citizens (NRC) and the political dispensation that has introduced them. Malviya starts by highlighting the guiding moral imperatives behind the Act, the intricate history of its genesis and the constitutional provisions from which it draws its validation. In this context, he refers to some of the oft-elided facts about the issues at hand, inter alia shedding light on the political volte-face from the detractors: the exercise of NPR and NRC are governed by the Citizenship Rules 2003, which was notified on 3 December 2004 under the Congress-led UPA. Further, the promise of granting citizenship to communities from Muslim-majority neighbors (Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan), all three with cruel histories of minority persecution, has long been a mainstay of the BJP’s election manifestos. The same holds true for the Article 35A too. Unless the protestors are of the opinion that electoral promises are not meant to be met, the debates should have started much earlier. Naturally, the sudden conflagration of demonstrators, shortly after the enactment of the CAA, took many by surprise, leading some to conclude that the protests constitute an insult to electoral wisdom of the citizens.

In the chapter titled ‘Is Secularism Under Threat?’ Malviya counters the allegation that CAA undermines the secular fabric of our constitution—a perception peddled persistently by all anti-CAA opinions. Quoting at length from the portions of Constituent Assembly Debates (CAD) wherein Nehru government’s position on granting citizenship to refugees after 19 July 1948 is probed, he argues that the founding fathers of our nation were “not keen to rehabilitate the Muslim refugees against the interest of the non-Muslim refugees.” Through an assortment of carefully measured assumptions and examples, Malviya insinuates that although Nehru’s stance was driven largely by the practical difficulties of rehabilitation, and that the Constitution of India does not imagine citizenship through the prism of religion, yet questions of religious identities were undeniably broached while discussing the refugee crisis. Further, in 1950, Nehru had inked a pact with Liaquat Ali Khan which mandated each country to take good care of its minorities. However, with Pakistan not holding its end of the treaty, as is evident from the dwindling population of the minorities in the Sunni-dominated state, it became morally binding for India to make special provisions for them. Naturally, as India sets out to relax the definition of ‘illegal migrants’ to accommodate the persecuted, religion emerged as the dominant category that the government had to think through.

The second part of the book tries to understand the changing dynamics of citizenship in the subcontinent by situating it in the larger history of immigration, territorial disputes, humanitarian crisis, post-partition exodus and yes, Israel-Palestine conflict too. He starts by dismissing the advocates of the CAA as agents of misdirection, calling attention to their ‘selective’ and ‘partial’ appropriation of Gandhi and Nehru. Further, he questions their notions of religious persecution, so very central to the conceptualization of the Act, and the exclusions of Muslims from the list of intended beneficiaries; shouldn’t the government be sympathetic to the cause of Ahmadiyyas and Balochs of Pakistan, he wonders. Over the past few years, following the acute humanitarian crisis triggered by the rise of militancy in the Middle East, the question of refugees has precipitated two kinds of responses: while the nationalists have expressed apprehensions about admitting refugees whose naturalization might pose a challenge, and therefore, a security threat, the left-liberals have argued for a considerate approach, invoking United Nation’s charter and principles of universal humanism. Perhaps, at some level, it makes sense to recast the conflict between the two positions as the ever-simmering tension between a ‘pragmatic policist’ and a ‘compulsive humanist’; the former has a duty to discharge towards the people who have elected him or her to power, while the latter has a point to prove, mostly a bohemian one. This does not imply that governors are unprincipled, but the simple fact that they are forced to make difficult pragmatic choices often makes them a suspect.

Khurshid comes from a celebrated political family. He is a distinguished scholar and the author of several books on the meaning of being a Muslim in a secular country. In works such as At Home in India (1986) and Visible Muslim, Invisible Citizen (2019), he has argued that the Muslims have long struggled with the burden of proving their loyalty of the nation. The ‘discriminatory’ clauses of the CAA, he fears, will make their painful memory of being constantly under suspicion sore again. Malviya, by contrasts, brings wisdom of a different sort to the debate. One gets the impression that his ability to engage with the entire gamut of charges—produce well researched rebuttals and the combative tenor of his arguments—draw upon his experience as the man-in-charge of the BJP’s formidable IT cell. Although we do not see in the book a transcript of a one-to-one interaction between the authors, which I dare say the readers would have greatly relished, the format succeeds in bringing the two around a set of common themes; both respond to the identity of the protestors, one calling them paid provocateurs, the other describing them as peaceful Satyagrahis; both reflect on the stipulation that identity of a citizen be established through documents, one calling it a standard practice, the other decrying it as discriminatory and anti-poor; both offer erudite glosses on Article 5 and Article 6 on the constitution, offering startlingly different readings on the constitutional validity of the CAA.

Could it be this attitude of persistent mistrust towards the state, whether justified or exaggerated, that lies at the root of most agitations, anti-CAA protest included? As one wades through the web of arguments that debaters on either side have woven, one gets the impression that there is an urge to mistrust the state and most of the things that it stands for. Scholars like Andre Beteille have demonstrated how this trust-deficit has paralyzed our institutions. With the discourse of rights drowning the discourse of duties, state becomes a force one needs to be perpetually wary of. The idea of state in ancient Indian political philosophy, as A.S. Altekar surmises in State and Government in Ancient India (1949), differs from modern (read western) thoughts on state in two significant ways. First, instead of emphasizing the rights of a citizen, ancient Indian commentators chose to elaborate the duties of a state, leaving the former to be inferred from the latter. Second, the ever-lurking modern suspicion, that projects that state as a hostile force inimical to the well-being an ordinary, is nearly absent in Hindu philosophy; each party abiding by its dharma (duty) leaves no ground for conflict. In Ramcharitmanas, Tulsidas offers a mediating proposition that helps diffuse logjams of the kind precipitated by the CAA debate. Speaking on the virtues of trust and love in political systems, he writes:

लोकहुँ बेद सुसाहिब रीति। बिनय सुनत पहिचानत प्रीति।।

lokahun ved susahib reeti। binay sunat pahichanit preeti।।

For Tulsidas, “a virtuous king is quick to recognize the love enshrined in earnest entreaties.” This, he avers, is the Vedic wisdom. Taking a leaf from Tulsidas, the protestors must establish communication with the government, and do so without malice or mistrust. The Citizenship Debate: CAA &NRC, which brings the two parties together on a platform, is a necessary first step in that direction.

Feature Image: Greater Kashmir

Thumbnail: Rupa Publishers

Tags :

Note: Your email address will not be displayed with the comment.